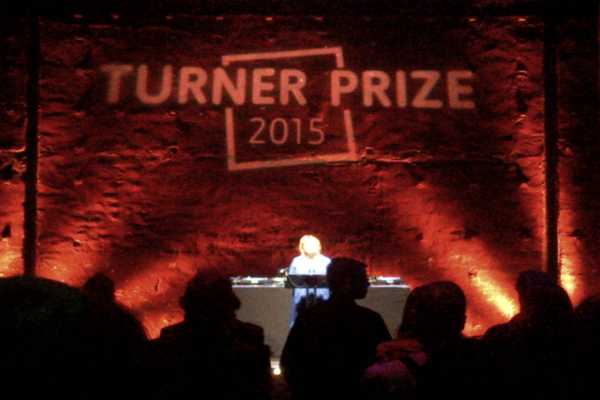

Granby Turner Prize

Turner Prize – truth behind the Toxteth terraces.

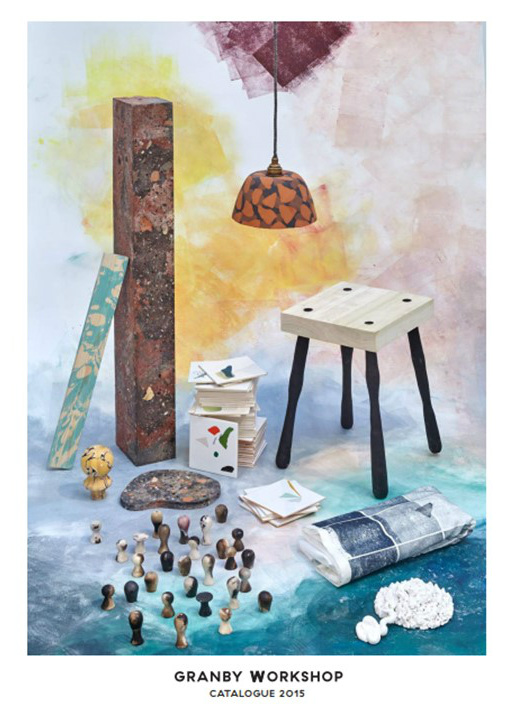

This is our Granby backstory. It features in Assemble’s beautiful Turner Prize 2015 catalogue – click here for a PDF:

15-10-07s Assemble Granby Turner Prize Workshop Catalogue

Why were the Four Streets emptied out anyway? A Granby back story….

By Jonathan Brown MRTPI, Share the City.org

September 2015

Granby’s Prince’s Park district in Toxteth, Liverpool 8 is a national treasure, whose treatment has for decades been a national disgrace.

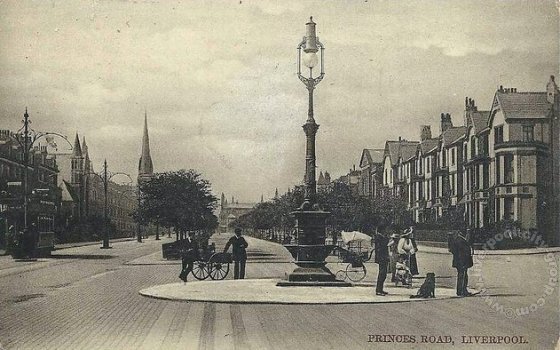

Princes Park was developed in the mid 19th century as a ‘Hyde Park of the north’ by the brilliant Crystal Palace architect Joseph Paxton, and the area laid out in subtle hierarchies by prolific Welsh masterplanner Richard Owens.

Early photograph of Liverpool’s grandest Victorian boulevard, Princes Road in Toxteth, Liverpool 8 c. 1900. Granby runs immediately off ‘the Avenue’. Picture: Liverpool-City-Group.com

The broad Victorian boulevard, dignified villas, tall ‘brownstone’ townhouses and classical brick terraces Paxton and Owens bequeathed Liverpool 8 enjoyed a cosmopolitan mid-20th century hey-day as the Brooklyn of Europe, until racist policing, economic collapse and crass housing policies sparked July 1981’s infamous uprising, for which the blighted heartland, Granby Street, appeared until very recently to be un-forgiven.

Britain’s Brooklyn – A West Indian man looks for accommodation in Liverpool in 1949. Photograph: Bert Hardy/Getty Images http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jul/06/before-windrush-review-race-relations-liverpool

Authorities euphemistically describe Granby as the “focus of sustained regeneration activity since the early 1970s”, code for interminable cycles of top-down displacement, dereliction and renewal, which have torn at the social fabric and fragmented Owen’s sophisticated street layout.

A small section of Princes Road and Avenue above Stanhope Street, Liverpool 8, from an aerial survey c.1930 – Granby is parallel to Mulgrave Street, running across the top of this picture. Pic Liverpool_City_Group.com

The spectre of Compulsory Purchase (CPO) has hovered over Granby for fifty years, ever since Liverpool’s 1966 Housing Plan condemned three-quarters of its inner city housing as ‘slums’ in need of clearance.

Entwistle Heights 1970 with Parliament Street and Granby to the right, showing the massive extent of clearance. Pic: http://www.liverpoolpicturebook.com/p/l8.html

Thirty years on from the uprising or riot the remaining residents have again risen up, this time in peaceful resistance against decades of destructive housing demolition and managed-decline.

In defiance of official delay and decay, the people have painted curtains on bricked-up bay windows, and planted emptied streets with trees, picnic tables and burgeoning vegetable boxes, eventually forming a community land trust able to fund a new future for their blighted streets.

Subverting council signs that warned the public to ‘Keep Out’, residents instead said ‘Come On In’ by setting up the thriving Cairns Street market, so summer Saturdays pulse with roots sounds, food stalls and vintage bric-a-brac, a little piece of Portobello Road in inner Liverpool.

In 2011, people from Granby’s surviving ’Four Streets’ mounted a week-long anti-bulldozer blockade to save large 19th century properties on Kingsley Road from removal by developer Lovells, Liverpool city council and social landlord Plus Dane. The ‘demolition coalition’ won – but Kingsley Road marked the end of clearance on Granby.

Liverpool 8 – where the sun shines onb both sides of the road: Housing Market Renewal as subverted and converted by Cairns Street residents – Pic Ronnie Hughes https://asenseofplaceblog.files.wordpress.com/2012/04/granby-4-streets.jpg

Since then, local and national housing policy has been turned round. Spending scarce money on destroying scarce housing looks especially stupid in a financial and housing crisis, a fact highlighted by such grass-roots campaigns, and the highly effective parallel work of national housing and conservation charities led by SAVE Britain’s Heritage and the Empty Homes Agency.

These were not the first acts of resistance against wrecking-ball regeneration schemes. As far back as the late 1960s, the housing charity Shelter worked with Granby residents on the innovative SNAP – Shelter Neighbourhood Action Project, an early attempt to stem the tide of clearance and bring empty properties back into use.

In the 1970s, SNAP helped spawn the first wave of local co-operatives and housing associations – bodies that, ironically, would often morph and merge over the next three decades from grass-roots providers into members of the clearance-crazed demolition-coalition they were set up to fight.

Granby Street’s thriving shops and street markets were stifled in the 1970s, severed from their sources of passing trade by a new estate concreted over the truncated Parliament Street end, where a massive compulsory purchase programme was clearing the way for the first sections of M62 inner motorway, a planning disaster mercifully never completed (the M62 today starts at junction 4).

Much of the modernist housing built across L8 at this time, like the deck-access Falkner Estate, high-rise Entwistle Heights and mid-rise Milner House, was so poorly designed and managed, and so alien to Liverpool’s traditional open door street life, that it lasted barely a tenth of the time of the terraced houses it replaced, and was demolished within 10 or 20 years of completion – leaving the city still paying for blocks long-since knocked down.

(Nick Broomfield’s 1971 short film of the clearances, ‘Who Cares’, is an essential document of those disruptive times: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/820087/ )

During the 1980s and 90s, the radical excesses of ‘high rise and highways’ planning were replaced by their conservative antithesis – the ultra-suburban, low rise and low density bungalows, semis and closes typical of the time – Brookside suburbs transposed onto Coronation Street inner cities, an approach still favoured by social landlords today.

Such cul-de-sac estates were at first designed defensively, like circled wagons, one way in and out, with walls around, the physical response to a climate of social breakdown and fear of crime in the wake of rapid depopulation and riots. Later layouts retain the low density but return to face the old main streets.

As homes these have been broadly popular and successful, but the price of steadying the ship has been a much lower population, smaller houses, disconnected walking routes and far fewer local shops and services – an artificially suburbanised inner city.

Though radically different architecturally, the common thread between all the top-down regeneration approaches since the sixties was the idea of ‘comprehensive redevelopment’ – the redlining of groups of streets for demolition and replacement, with eviction and acquisition by compulsion if need be.

In the early 1990s Granby residents won a crucial CPO Public Inquiry after another long running battle against comprehensive demolition, but not before the ten streets defining the central section of Granby were lost.

The late Dorothy Kuya (1931 – 2013) took a lead role in bringing the bulldozers to a halt before they reached the final four streets – bequeathing us the only section of historic Granby that survives today.

Dorothy described the demolitions as a deliberate policy to disperse the black community.

“What has happened here is a scandal,” she said. “It is not only decent homes that have been destroyed, it is a whole community.”

She was particularly scathing about the new suburban housing that was put up to replace the demolished homes, saying they were “pokey and cheaply built” and already looking the worse for wear.

Four streets were eventually saved. So a victory of sorts, I ventured. “We may have won the war but many were killed,” replied Dorothy in her characteristically terse fashion.

Interview with Dorothy Kuya by Angela Cobbinah in Black History 365 magazine (see ‘Ghost Town’ from October 2011), quoted in https://angelacobbinah.wordpress.com/2013/12/28/dorothy-kuya-rip-1931-2013/

By the late 19990s, with the old Granby decimated but the CPO apparently resisted, it seemed that sanity would ultimately prevail in the final four streets – Beaconsfield, Cairns, Jermyn and Ducie.

This appeared confirmed when in 1998 the beautiful renovation of the north side of Beaconsfield Street was completed, costing a mere £15,000 per house. Refurbishment was carried out without evicting existing residents, holding out hope that Liverpool Council and local social landlords had embraced the advantages of restoration as opposed to redevelopment.

But in the early 2000s, the tragedy of post-war clearance returned to Granby, in the expensive farce of John Prescott’s ‘Pathfinder’, the £2.2bn so called ‘housing market renewal’ (HMR) programme. Pathfinder aimed to lift low house prices by reducing the number of houses – just at the moment the economies and populations of northern cities were recovering from their post-industrial collapse, and city living was back in vogue. It was a cure worse than the supposed disease.

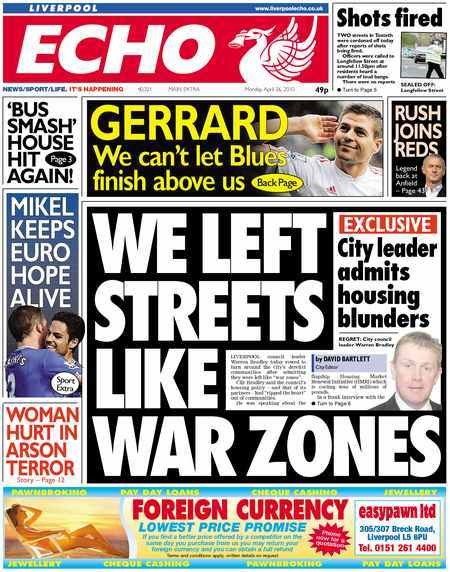

Council Leader: “We ripped heart out of Liverpool communities” – Liverpool Echo, 26th April 2010

http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/council-leader-warren-bradley-ripped-3426650

The essence of ‘Pathfinder’ or ‘Housing Market Renewal’, was to use public money to buy up, board up and bulldoze terraced properties across the north of England, emptying occupied homes so their land could be handed to private housebuilders and social landlords for redevelopment at much lower densities. Merseyside’s delivery quango, one of nine in England, was called New Heartlands, run by Professor Brendan Nevin, the academic champion of HMR. It was soon dubbed ‘New Heartbreak’, and ‘New Wastelands’ by locals. Even its political champion John Prescott admitted ‘they knocked the whole bloody lot down, so you had bomb sites everywhere’, while the Council Leader Warren Bradley who oversaw the policy lamented it had left communities looking like ‘war zones’.

Such was the fate of Granby. Pathfinder effectively imposed a further decade of ruinous planning blight on the four streets, during which time the homes were emptied out further, offers of investment were refused, and the buildings left in such extreme disrepair that the south side of Ducie Street was demolished, and corner shops on the Granby junction left close to collapse.

There is little doubt that, despite the resilience of residents, these streets would not have survived the 2000s were it not for the ten year national pro-refurbishment campaign by conservation charity SAVE Britain’s Heritage and housing charity Empty Homes. These charities helped link the disparate local anti-demolition groups across northern England to national media support, and opened up lobbying routes to MPs and government ministers. In an attempt to bring their story to outside attention, I personally toured the ghost streets on numerous occasions with dozens of journalists, politicians and potential investors, introducing residents to anyone who might help. We even gave tours to David Cameron and Michael Heseltine, and through SAVE discovered eventual project backers Xanthe Hamilton and Steinbeck Studios, who brought in Assemble.

SAVE helped gain massive publicity about Pathfinder’s role in Liverpool through ITV’s Sir Trevor MacDonald and Channel 4’s George Clarke ‘Housing Scandal’ documentaries, and attracted interest from journalists across the political spectrum, notably Charles Clover of the Sunday Times and Telegraph (3rd May 2005), Ed Vulliamy at the Observer (3rd July 2011) and Ciara Leeming and Sir Simon Jenkins of the Guardian (16th March 2007).

In fact SAVE went further still – this tiny charity, with just 3 full time staff, not only took the Coalition government to the High Court over demolition and won, but put its scarce resources on the line, buying the last inhabited house in nearby Madryn Street, the Liverpool 8 birthplace of Beatle drummer Ringo Starr, and worked with Wayne Hemingway to make an affordable, attractive home for a local couple – a prototype for Assemble’s work across Granby (Liverpool Echo, 16th June 2014).

This consistent pressure for retention of terraced streets helped force an end to the Pathfinder demolitions, and in 2011, quoting our report for SAVE, the Housing Minister informed Parliament of a formal switch in government housing policy to favour renovation and self-build, effectively bringing a reprieve for Granby. After two false starts under city council favoured outfits ‘Leader One’ (Liverpool Echo, 1st Nov 2012) and the very curious ‘Fringe’ developments (see Private Eye 9th Aug 2013, Issue 1346), the community wrested back a stake in the Granby triangle. SAVE had introduced philanthropic social investors Steinbeck Studios to the Community Land Trust, who in turn introduced architects Assemble – and the rest is now Turner Prize history.

15-10-07s Assemble Granby Turner Prize Workshop Catalogue.PDF

A footnote: The adjacent Welsh Streets are by the same architect as Granby’s Four Streets, the Welsh masterplanner Richard Owens. The 500 or so houses are located in the same Princes Park ward and L8 postcode, and are also in council and Plus Dane ownership. While Granby’s renovation is Turner Prize nominated, Liverpool council still hold empty hundreds of homes on the Welsh Streets for demolition. In January 2015, Liverpool Council’s CPO on SAVE’s Madryn Street house in the nearby Welsh Streets was refused by the Secretary of State, a decision the city has vowed to challenge. The Public Inquiry heard evidence that the average home would need £40k to repair the damage done by Pathfinder, but be worth twice that if renovated. A FOI request revealed the Council had officially devalued properties there to just a few hundred pounds.

The contrasting prospects of these identically designed houses should be studied by everyone interested in the story behind the Turner Prize nomination.

(Thanks for reading – I’ll be adding more images to this post and tidying it up over the next week or so – comments welcome)

Eleanor from Cairns Street with Maria and Fran from Assemble at the Granby Turner Prize 2015 party in Glasgow’s Tramway Gallery

Assemble’s Granby Turner Prize Installation in Glasgow is a life size shell of one of Owen’s terraced houses

Turner Prize 2015: The replicated shell of a Liverpool terraced house in Glasgow’s Tramway Gallery becomes a grand showcase for Assemble’s Granby4Streets workshop products

“In order to save the village, it became necessary to destroy it.”

This comment from an American commander in Vietnam (taken from an article on the language of terror and war in the Guardian), rather chillingly sums up for me the mindset of the various ‘demolition-coalitions’ which have haunted these Liverpool streets for countless decades. As your article shows, the area has been a living testament of how those in power have actively chosen to destroy it -time and time again -‘in order to save it’ – with no regard for civilian casualties or collateral damage.

Only now, after Assemble’s deserved triumph, does the narrative that the village does not, in fact, need bombing emerge into the mainstream as a possible alternative. Let’s hope that the history books will not judge Assembles’ victory merely as a brave choice for the Turner Art Prize but as a definitive turning point in L8’s fortunes. For this to happen any analysis surely needs to include the wider context that your article provides.