Cruise Liners Come Home to Liverpool

Liverpool invented and perfected the luxury liner – and then saw them depart, apparently for ever.

Now, like migrating birds, they are back. In the 10th anniversary year of the new Cruise Liverpool terminal, we reflect on their return, and its meaning for the city.

Fred Olsen was the first line to fully commit to Liverpool’s cruise revival. Here, 28,400 ton Boudicca waits to depart Liverpool’s floating landing stage on a calm winter’s afternoon in January 2017. The ‘mini QE2’ was about to embark on an epic 80 day voyage round South America, after 16 Liverpool departures through 2016. Pic. SharetheCity.org

French line Ponant’s Le Soleal mega-yacht on her first visit to Liverpool in 2015. Picture by Andy Teebay, courtesy of Liverpool Echo. Full picture gallery here.

The female ‘Lyver Bird’ looks out to sea over Liverpool’s Cruise Terminal into a warm summer sunset – stunning drone footage from (c) ICARUS UAV – used with kind permission.

Cruise Liners Come Home to Liverpool

Jonathan Brown, SharetheCity.org

January 2017

Liverpool’s mythic ‘Lyver Birds’, perched 330 feet above the waterfront cruise terminal, overlook all arrivals by land and sea, the city’s shamanic protectors. As with the ravens at the Tower of London, tour guides claim the city will fall if these exotic birds should ever take flight.

That seems unlikely given that Liverpool’s giant cormorants are made of gilded copper, and chained fast to concrete domes. Nowadays, as they watch over crowds swirling happily across the Pier Head for selfies with the Beatles statues, and punters queuing far below for Mersey ferries and funfair rides, a civic fall seems happily distant.

Liverpool’s Pier Head bustles on 16th August 2016 – 113,000 ton Caribbean Princess is moored at the floating landing stage, with the ‘Lyver Birds’ looking on from their clock towers. Pic. SharetheCity.org

But not so very long ago, from the early 1970s into the new millennium, it felt perhaps that Liverpool would fall – indeed, had fallen – shaken to its soul by the sudden, and seemingly final, departure of another exotic breed of metal sea bird, the ocean liner.

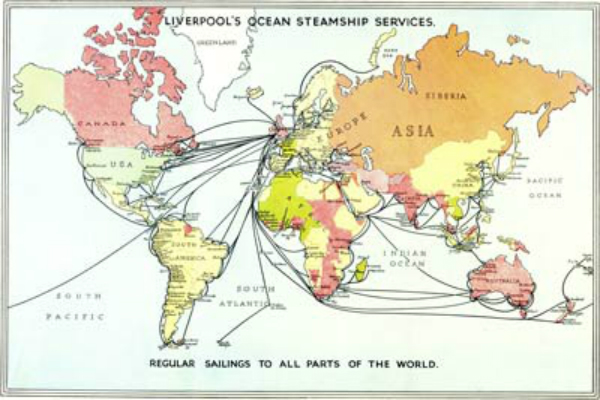

World map showing regular steamship ‘lines’ from Liverpool to all parts of the world, when the city was the JFK or Heathrow of the seas (Pic. Liverpool Museums, 1920s).

Ocean liners were elegant creatures that first evolved on the wide Atlantic between Liverpool and New York in the early 1800s, under sail and then steam, taking our city’s name to the farthest corners, and highest societies, of the globe, for over 150 years.

The world’s first scheduled inter-continental passenger services were the four Black Ball Line ‘packet ships’ (Amity, James Monroe, Courier and Pacific) between New York and Liverpool. The service started in 1817 and ran for 60 years. Pic. TheEsotericaCuriosa

- ACL Cargo liner ‘Atlantic Sea’

- 100,430 gr. tonnes

- Christened at Liverpool 20th Oct 2016

A ‘liner’ can carry cargo or passengers – sometimes both – and, to be strictly accurate, only refers to ships that normally ply direct ‘line routes’ between distant ports, to a regular timetable, like a railway line. Ships with more peripatetic lives are sometimes called ‘tramps’, operating without a schedule.

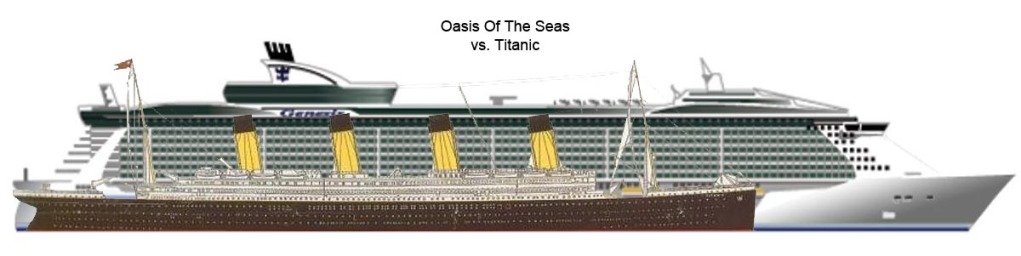

Modern cruise ships are scheduled, but take passengers on circuitous leisure routes, often beginning and ending in the same port, sometimes in calmer, shallower seas like the Med. They are constructed differently to true liners, prioritising passenger numbers and vacation facilities in tall super-structures, rather than speed and long range seaworthiness of the older ships.

Think high and wide versus long and low.

High and wide vs Long and Low – Royal Caribbean’s 2009 Oasis of the Seas to scale with Liverpool’s 1912 RMS Titanic. Approx. 225,000 g.t. vs 46,000 g.t.

- Fantail stern shows Boudicca’s ocean liner pedigree

- Sharp bows to cut Atlantic waves

- Classic portholes and deadlights

Classic cruise liners like Black Watch, Boudicca, Albatross and Marco Polo are an interesting and precious link between the two types, strong, elegant ships built to ply former ‘line routes’ and luxurious distant circuits on the high seas, now converted for the 21st century mainstream cruise market, but still reassuringly capable of cutting through the roughest of waves.

The last true purpose-built ocean liner. Cunard’s Queen Mary 2 on the Mersey in 2015, passing the derelict wooden stub of Liverpool’s historic Princes Landing Stage en route to the new Cruise Terminal. Pic. courtesy Peter Elson.

With air travel now so fast and affordable, Cunard’s Queen Mary 2 is the world’s only remaining true passenger ocean liner, and even she is really a hybrid cruiser, but there are of course still innumerable cargo and ferry lines criss-crossing the seven seas, with ACL, P&O, Stena and Bibby’s staying loyal to Liverpool, and Danish line Maersk locating its UK HQ here.

QM2 and classic cruise liners like those mentioned above are a rarefied bridge between the ‘golden age’ of true liners that ended in the 1970s, and the leisure cruisers of the 21st century.

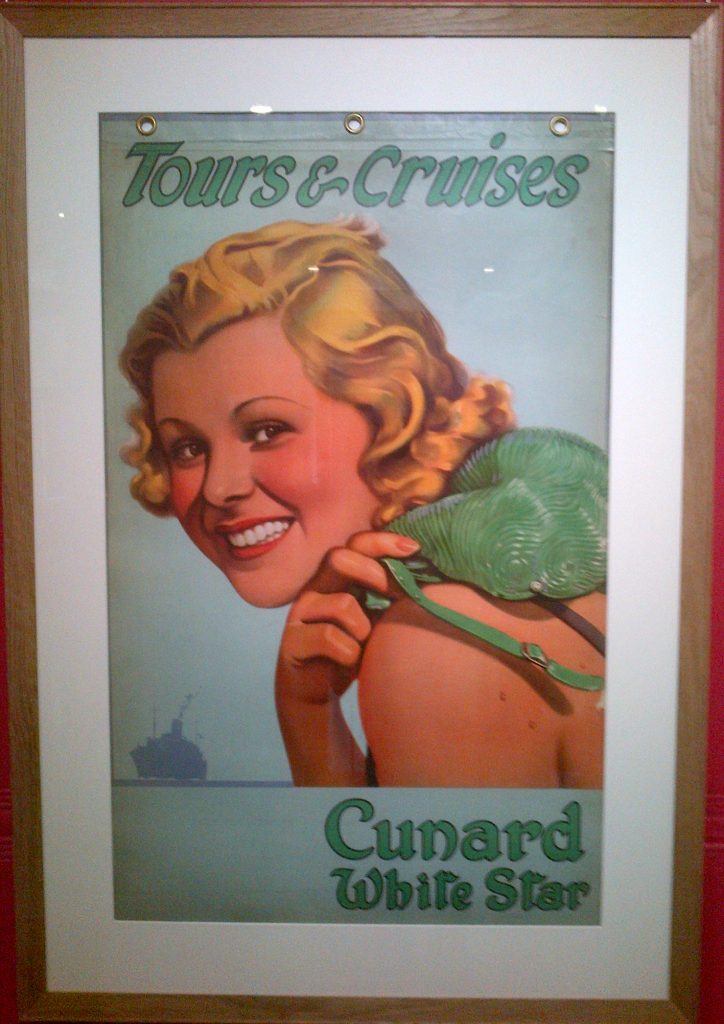

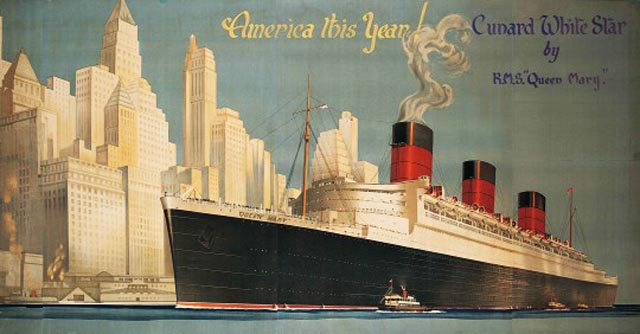

Original Cunard White Star Tours and Cruises poster in Liverpool University Victoria Museum and Gallery – both lines were founded and headquartered in the city. Pic. Share the City.

‘Disa-Pier Head’ – the dark years

Prior to the jet airliner’s rapid ascendance in the 1960s, Liverpool was the world’s premier ocean liner port, the Heathrow, JFK or Schiphol of the seas, with more scheduled services, and a larger, faster and more modern fleet than any harbour on earth.

Liverpool registered Cunard White Star ships in New York – original poster in Liverpool University’s Victoria Museum and Gallery. Pic. Share the City.

White Star’s RMS Olympic pays a courtesy visit to her registry port of Liverpool on 1st June 1911, having just witnessed her infamous twin Titanic launched in Belfast, across the Irish Sea. A third sister, Britannic, followed in 1914. Pic. RMS-Olympic DeviantArt.com

Liverpool held its top position for some 200 years, and although Southampton took much of its trans-Atlantic traffic as the 20th century progressed, Britain’s most prestigious liners continued to be ‘home-ported’ and crewed on the River Mersey, even when they – like Titanic and Queen Mary – never actually visited.

Four times Olympic gold medallist Jesse Owens and his wife Ruth are welcomed back in New York aboard the Liverpool-registered Queen Mary. Pic. (c) Bellmann Archive

Hollywood stars, impoverished emigrants, old and new money, statesmen, sports stars, artists and royalty, prisoners and GIs, all travelled the globe aboard Liverpool vessels.

The dream Queen – ‘Elizabeth’ of 1938 was even larger and faster than ‘Mary’ of 1934. Robert Lloyd’s painting shows her approaching Cunard’s Pier 90 terminal on the Hudson River. LiverpoolShips.org

Spanish Aznar Lines operated Liverpool’s last long distance passenger liners, prior to the 21st century Cruise Terminal. This shows their stylish cruise-car ferry Monte Toledo at Santander during the 1970s. Pic. by kind permission of Ian Boyle, Simplon Post Cards.

Liverpool ships and crews were utterly integral to allied victory in WWII. The merchant marine convoys, with naval and air support, broke the six year axis U-boat and air bombing blockade to supply the besieged British Isles (and Soviets) with over 1,000,000 tonnes of supplies a week from Canada and the USA. The ‘Battle of the Atlantic’, documented in Nicholas Monserrat’s ‘Cruel Sea’, was the longest continuous military campaign of the second world war.

The cost in blood and tonnage was profound. 3,500 civilian ships and 175 warships were lost, many based in Liverpool, where the battle was directed. A third of the world’s merchant ships were British, and a quarter of the crews came from the wider Commonwealth including India, Africa, Hong Kong and Canada – the battle was a global endeavour.

Churchill, who ‘crossed the pond’ several times during the war on RMS Queen Mary thanks to her ability to outrun submarine ‘wolf-packs’, said:

“The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome.”

The post-war years saw a return to the golden era of captain’s dinners, balloon parties and promenades on deck, and a new generation of Liverpool crews stewarding wealthy passengers and ‘ten pound Poms’ on voyages across the seas, assimilating the cultures and pleasures of distant port cities.

But as the swinging 1960s segued into the oil-shocked 70s, Liverpool was hit by a perfect storm of air travel, containerisation, the decline of northern manufacturing, and Britain’s turn towards Europe and away from its Atlantic, African and Asiatic Commonwealth.

Cunard had headed for Southampton in 1966, and in 1971, the last Canadian Pacific trans-Atlantic liners departed, seemingly never to return. Elder Dempster Lines MV Aureol closed the last service to West Africa in 1972. Only Spain’s Aznar Line kept faith with Liverpool, offering a Liverpool-Canaries service through the decade, but its modern Monte Granada and Monte Toledo cruise-ferries were sold to Libya in 1977.

Most cargo lines switched to container ports along England’s continental seaboard, or the European mainland, and for miles along the Mersey, the most extensive dock system ever built was increasingly left to the seagulls and silt.

Liverpool’s sublime granite seawalls fell silent.

- World Heritage Site

- The Industrial Venice

- Imperial Mausoleum

Massive external economic forces were compounded by some terrible local decisions, most culpably a traumatic mass population clearance from the waterside working class communities that still scars the inner city to this day.

Gateway to Empire – the remnant of Princes landing Stage, Liverpool, 1986. Pic. (c) Steve Howe, Chester B & W Picture Place www.bwpics.co.uk – used with kind permission.

Depopulated and without big ships, the empty seaport was bereft, an industrial Venice in winter, the mausoleum of Britain’s lost maritime empire.

Between WW2 and the millennium, Liverpool’s core population halved, and the UK government planned secretly for ‘managed decline’, a staged abandonment of the city.

- Titanic

- Queen Mary

- Mauretania

- Queen Elizabeth

- Lusitania

- Great Eastern

Such a fall from grace for the place that owned Titanic, Lusitania, Mauretania, Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth and Great Eastern. Fleets of the most famous craft ever to set sail carried Liverpool’s name across the globe on their stern, and the world’s wealth to the city.

Empress of Canada – the ship! – at Gladstone dock Liverpool, mid 1960s. Pic. (c) David A. Halsall, used with kind permission of Peter Halsall.

Black Ball’s Boston built ‘Extreme Clipper’ James Baines of 1854 connected Liverpool to Melbourne, Australia. “She is so strongly built, so finely finished and is so beautiful a model that even envy cannot prompt a fault against her. On all hands she has been praised as the most perfect sailing ship that ever entered the river Mersey.” Pic. Robert Frew

Started with the Black Ball line in 1817, improved by Samuel Cunard’s first year round steamship Britannia on July 4th 1840, and perfected in the golden era of jazz and art-deco, trans-Atlantic passenger liners were Liverpool’s love affair with the world.

The River Mersey and Port of Liverpool Building from the roof of the White Star HQ, where Titanic was owned and registered. Cunard’s historic HQ is just out of shot to the right. Pic. Share the City

Their designs were shaped and signed off in palatial office fortresses on the waterfront. In turn, maritime architecture was carried through to city buildings, still visible in interiors like those of the Adelphi Hotel and former George Henry Lee department store.

A vast economic infrastructure was built round the sea. Liverpool had pioneered the first railways in order to distribute cargos and people, and developed mighty networks both sides of the river. Until oil replaced coal after WW1, a ship like Mauretania would devour 500 railway wagons of coal while crossing the Atlantic (a century on, fueling a ship is still called ‘bunkering’).

It is said that just keeping the linen sheets, towels, table-cloths and napkins bright white gave work to 300 laundries across Liverpool.

Culturally, the daily trans-shipment of ideas across oceans gave Liverpool an edge that was to cut through most explosively in the Beat era, as the fashion and music tastes of young ‘Cunard Yanks’ reverberated back across the Atlantic. It’s probably no coincidence that John Lennon, son of a sailor, was so creative in the great seaports of Liverpool, Hamburg, New York and London.

Liverpool’s last trans-Atlantic liner – Canadian Pacific’s Empress of Canada – at the Princes Landing Stage, 1960s. Pic. LiverpoolShips.org

Losing the liners with the Empress of Canada’s last service in December 1971 was an existential catastrophe, like Seattle losing Boeing and Microsoft, or London losing the City banks.

One of Britain’s wonders – Liverpool’s splendidly restored Albert Dock in the UNESCO World Heritage Site. Pic. Craig Easton, Visit Liverpool.com

Since the 1980s Liverpool has fought a spirited battle to reinvent itself as a centre of culture, tourism, shopping and higher education, salvaging the Albert Dock, building a superb shopping centre and cleaning up the river, but the scarcity of great passenger ships on the Mersey continued to corrode its essential identity.

Sporadic false starts were made to entice them back. Like rare sightings of migrating birds blown off course, a handful of cruise ships occasionally chanced a stop, as if visiting the wreck of their former flagship.

Where’s there’s muck there’s brass – Liverpool’s pre 2007 ‘cruise terminal’ was in Langton Dock’s alpine scrap mountains. This is the view from the river entrance. Pic. courtesy of Chris Allen, Wiki-commons.

With the Princes Landing stage reduced to a stub in 1974, such guests were forced miles downriver, amid grubby coal and scrap yards round Langton Dock, scuppering memories of the marbled lounges of the belle époque.

From Glasgow to the Gulf. Cunard’s supremely graceful QE2, launched 1969. Pic. of the ship retired in Port Rashid, Dubai, 2010, by kind permission of Gabriele Goldbeck. TheQE2Story.com

Cunard’s beloved ship of state, RMS Queen Elizabeth 2, was launched on the Clyde in 1969 and had been partially designed and conceived in Liverpool. But with Cunard’s move south in 1966, she was Southampton-registered, unlike her Liverpudlian predecessors, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth. QE2 took 21 years to pay a visit to the company’s founding port, obligated by the line’s 150th anniversary in 1990.

A million people lined both sides of the river Mersey to witness the fleeting sight, including generations of former ‘Cunard Yanks’ and other merchant mariners, a bitter-sweet celebration of all that had been launched and so recently lost from these shores.

The trickle of annual visits by occasional cruise ships continued through the 1990s into the new millennium, the returning pioneers building a precarious crow’s nest from which to seek sustenance among the cliffs of rusting iron.

A real liner – Marco Polo, launched for the USSR in 1964 still going strong as a Cruise and Maritime favorite. Pic. Cruise and Maritime.

Intriguingly, Russian-owned ‘Charter Travel Club’ (CTC) showed especially enterprising spirit as the USSR broke up, chartering tough Soviet-built ships like the Alexander Pushkin (still going strong today as Cruise and Maritime’s Marco Polo) for 3 visits to Liverpool and Greenock (for Glasgow) in 1992.

Style and substance – MS Marco Polo in its original life as ocean liner Alexsandr Pushkin, on the (sometimes icey) Leningrad-Montreal run during the mid 1960s. Pic. courtesy of Simplon Postcards

On the hunt for hard currency, the Russians therefore helped pioneer the return of cruising from Britain’s great northern ports, appropriate given Liverpool’s long links to the Baltic.

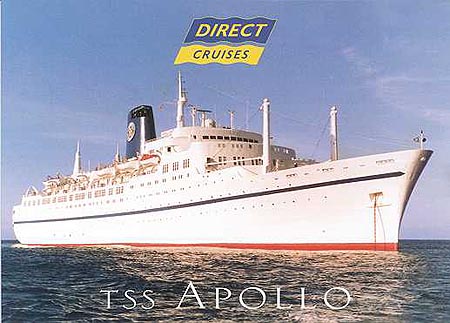

Liverpool’s last golden age trans-Atlantic liner, the Empress of Canada, made an all-too-brief cameo comeback as the TSS Apollon in 1999. Pic. LiverpoolShips.org

An even stranger vision for ship-spotting ‘twitchers’ came on 30th May 1998, when the beautiful Empress of Canada, which ran Liverpool’s last ever trans-Atlantic line route for Canadian Pacific, re-appeared like a maritime phantom as T.S.S. Apollon, 27 years since she’d brought the curtain down on the golden-era.

Direct Cruises had spotted the potential of services from north Britain and looked set to clean up, with Apollon making several turnrounds – but were then swallowed by Airtours, and their noble cruise project sank in 2000.

Intriguingly, after her 1971 leaving of Liverpool, the ‘Canada’ enjoyed a long afterlife prior to ‘Apollon’, sailing as as MS Mardi Gras, Ted Arison’s pioneer ship for Florida’s nascent Carnival Cruises.

Regular visitor Caribbean Princess at Cruise Liverpool in May 2016. At 113,000 g.t. she carries over 3,000 guests and 1,200 crew. Pic. SharetheCity.org

From this tiny operation grew the almighty Carnival Corporation, with a fleet of over 100 vessels, a portfolio of 10 major brands (including P&O, Cunard and Princess), and around half the global market, a growing slice of it based here.

The Empress of Canada, built on the Tyne in 1961, was therefore another golden thread bridging the two eras of Liverpool liner travel; the last of the scheduled Atlantic services, and the first of the new leisure cruise empire.

Passengers enjoying the shapely fan-tail stern of Fred Olsen’s Boudicca as she prepares to depart Liverpool for Dublin and Cobh in December 2016. Pic. SharetheCity.org

Fred. Olsen was the first blue-chip shipping line to seriously commit to re-establishing a permanent cruise base in Liverpool, and should also be credited with stirring – perhaps shaming – the city into investing in proper landing stage and then turnaround facilities at the Pier Head.

The cruise operation of the established Norwegian firm is a UK company based in Ipswich, and in 2004 launched regular Liverpool sailings of its much-loved ‘ugly duckling’ the Black Prince, and quickly built a loyal following of repeat passengers, proving the business case.

Olsen’s success, and a growing sense of civic self-confidence as Liverpool approached its year as ‘European Capital of Culture’ in 2008, spurred the opening in September 2007 of a new £19m floating landing stage, designed to reinstate the ‘in river’ infrastructure removed 35 years earlier, and thereby allow the biggest passenger ships in the world to once more tie up alongside the now UNESCO protected Pier Head World Heritage Site.

This investment marked the return of regular cruise ship visits, but an arcane bureaucratic imbroglio over European Union funding restrictions meant the landing stage did not see the start and finish of a true Liverpool ‘turnaround’ cruise for another five years.

December sunset on the Mersey viewed from Boudicca’s pristine teak decks and mahogany rails, before her last turnround of 2016. Pic. SharetheCity.org

Again, Fred. Olsen proved catalytic – their investment in larger sister ships Boudicca and Black Watch to replace the tiny Black Prince was undertaken on the understanding they could soon leave Langton Dock’s scrap mountains and escape its tight, time-consuming and tide-ripped locks to berth right in the city’s UNESCO World Heritage heart.

One stormy night in 2008, Black Watch was refused permission to use the shiny, empty, expensive new landing stage because of red tape. It was the last straw – Olsen’s marketing director Nigel Lingaard told Liverpool to get it sorted, and pulled his ships out for the 2010 to 2012 seasons, citing ‘scrapyard scenery and abysmal passenger facilities’.

He told Peter Elson of Liverpool’s Daily Post: “We find it virtually impossible to explain to potential customers why Liverpool has a much-heralded new cruise berth, which lies idle while we are berthed in a dismal industrial area. Customers don’t care about local politics, and deserve better.” (Nov 28th, 2008).

Liverpool’s press rose to the challenge. Our good friend Peter Elson, a leading maritime journalist and author, led the ‘Get Back on Board’ campaign that went all the way to Downing Street.

Iceni ships – the bronze figurehead of Celtic warrior Queen Boudicca on her namesake ship. Pic. Share the City.org

Eventually, heads were knocked together, grants were partly repaid and the mandarins placated. Cruises could begin and end on the river Mersey again. The first turnaround took place in the summer of 2012, and the Olsen line stationed MS Boudicca and her sisters Black Watch and Braemar in the city for year round scheduled sailings.

After 40 years, Liverpool was a true cruise line port once more.

In the short time since, Liverpool has established itself as Britain’s favourite port of call for the influential ‘Cruise Critic’ editors, and is rated one of Europe’s most desirable destinations by passengers.

Gareth Jones’ brilliant shot from Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral tower captures the Cunard Three Queens and Red Arrows in perfect formation at precisely 1.50 pm on Bank Holiday Monday May 25th 2015. (c) Gareth Jones, used by kind permission.

In 2016 Fred Olsen accounted for around a third of the 61 sailings, while Carnival, Cruise and Maritime, Thomson, Cunard and Disney have joined Olsen’s ships in running both regular visits and scheduled ‘turnaround’ cruises.

Cunard paid full respect to the 175th anniversary of its Liverpool foundation with the joyous ‘Three Queen’s Visit’ in May 2015, documented on our website in this entertaining guest article by Peter Elson.

Italian American – on her first call to the city the 84,000 ton, Fincantieri-built Disney Magic leaves the Liverpool landing stage in a flat calm on 27th May 2016. The ship is now paying regular visits, to the delight of Merseyside’s children. Pic. SharetheCity.org

The range of destinations one can sail to in comfort from Liverpool is now almost as far flung as those advertised in the classic posters of the golden age. They include Venice, Istanbul, Zanzibar, the Canaries and Azores, Madeira, the Black Sea, Norwegian Fjords, Iceland and the rugged coasts of Ireland and Scotland.

Even more importantly for civic psychology, Liverpool is again a trans-Atlantic passenger port. In May and August 2015, Fred. Olsen’s Black Watch ran two successful return cruises from Liverpool to Canada, reviving the route that helped make the city great, but which had been unsailed except by freighters and naval warships since 1971.

Cunard followed suit, crowning its ‘Three Queens’ visit with an equally historic anniversary departure of the Queen Mary 2 on July 4th, bound from Liverpool for Boston and New York via Halifax Nova Scotia, 175 years to the day since the Canadian founder Samuel Cunard had departed Coburg Dock on his seminal steamship Britannia in 1840.

Disney Magic at the Cruise Liverpool terminal, viewed from an unphased Mersey Ferry, May 2016. Pic. Share the City.org

Now it is again becoming familiar, though no less wonderful, to see a fully sold out passenger ‘megaship’ arriving on the Mersey from Cape Canaveral in Florida, or calling on a regular 12 day circumnavigation of the British Isles during summer.

In June 2017, Boudicca sails for Bermuda to view the America’s Cup, and in October passes through Suez to the Indian Ocean from Liverpool, on a 47 night passage. Quite something when in 2006 the only boats leaving the Pier Head were for Birkenhead, Douglas and occasionally Llandudno.

Boudicca’s route for the 26 night America’s Cup trans-Atlantic cruise from Liverpool in June 2017. Details from Fred. Olsen website – click here.

With around 60 cruise ships arriving this year, and a mayoral target of 100, Liverpool is some way off Southampton’s 300 departures, and of course great ships are no longer built and crewed on the Mersey, Thames, Lagan, Clyde and Tyne.

Yet growth and customer satisfaction levels under the Cruise Terminal’s energetic leader Angie Redhead and her dedicated team have been sufficiently high to commit the city to building a proper terminal to replace the cheerful marquee that currently greets passengers, and evoke still more of the glamorous spirit of the heyday. Also, Peel Holdings’ much awaited Liverpool Waters project may yet see a second landing stage and terminal installed by the central docks, where a new stadium for Everton FC is also proposed.

Shore excursions from Liverpool Cruise Terminal show guests the Beatles story of Strawberry Fields, Penny Lane and the Cavern Club, and also head further afield to Roman Chester, the Lake District National Park and the castles and mountains of North Wales. Pic. SharetheCity.org

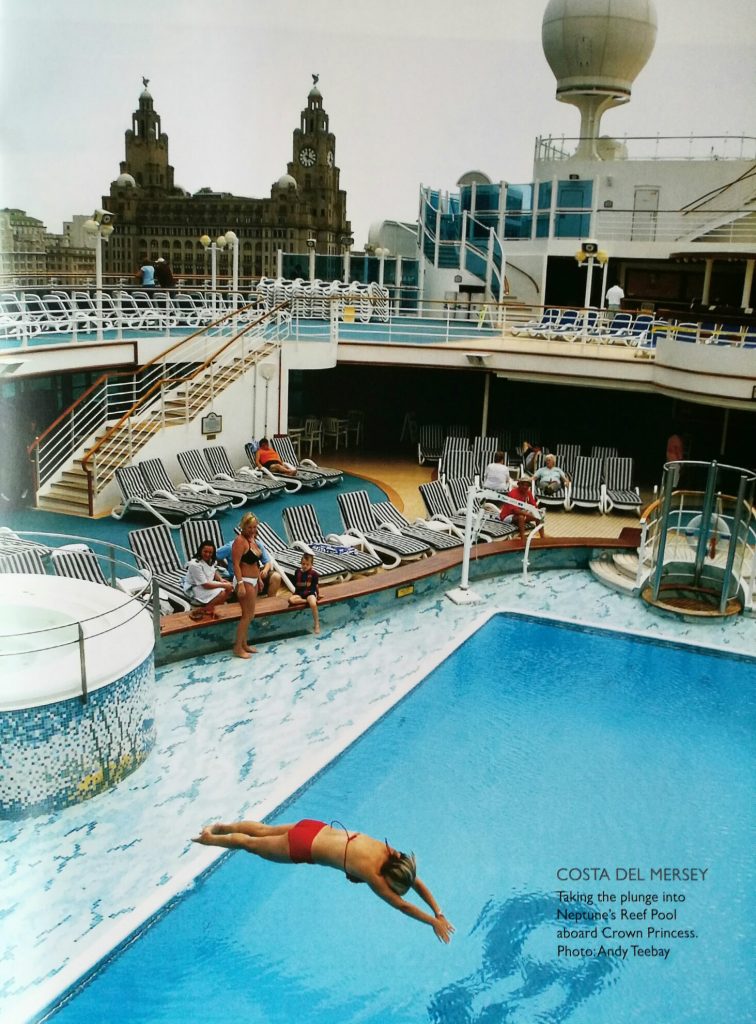

Costa del Mersey. ‘Neptune’s Reef Pool’ on board Crown Princess. Pic. Andy Teebay, courtesy of Liverpool Echo. From Peter Elson’s book ‘River Mersey Gateway to the World’.

The psychological and spending power of liners bringing thousands of passengers from Cape Canaveral and Canada, with dozens of coaches dispersing day-trip shore excursions to the castles of North Wales, the Roman walls of Chester and the mountains of the Lake District via Beatles Liverpool, is profound for a place that for two generations had feared its best seafaring days were behind it, and faced a future of perpetual decline.

Phoenix rising – 330 feet up in the Gods, two giant copper birds by German sculptor Carl Bartels keep watch on top of Liverpool’s Royal Liver Building. Drone image (c) ICARUS UAV – used with kind permission.

Now the Liver Birds are again seen from the tidal waters by passengers visiting Britain from across the western hemisphere, and watch over Britons leaving to see the world from Liverpool.

Their shamanic spirits must delight that the stately seabirds once thought extinct on these shores have returned, importing good fortune, and exporting happy memories.

Ends.

Useful Links – current Liverpool cruise ship information:

Cruise Critic Member Reviews of Liverpool

Cunard – Back Where they Belong

Useful Links – historic Liverpool cruise ship information:

Cunard Queens – past and present

Simplon Postcards – superb image archive

Black and White Picture Place – Images of Liverpool

SS Maritime.com – The 5 Ivan Franco or ‘Poet Class’ Soviet Liners

So good to see the big passenger ships back on the river

As a Chinese scouser born in the ozzy down Myrtle St but now residing in a distant hinterland known as London, I cast myself as another rare exotic bird that has set sail and migrated from its ancestral home.

The demise of Liverpool’s civic psychology since my departure is well documented – but the travesty that was the migration of ocean liners from Liverpool’s majestic docks, less so. Well done for putting this right, Jonathan, and for so beautifully capturing their triumphant return!

I can now feel the deep winds of homecoming calling me back too!

Should read

“The demise of Liverpool’s civic psychology RESULTING FROM my departure…”

Let’s not beat about the bush about this!

A great article charting a fascinating maritime story. I will certainly look at the Liverpool waterside with renewed interest.

Thanks for reading it through and for your kind comment Ashley.

Epic article. Wave after wave of fantastic facts.

Deeply knowledgeable writing, with pictures in a league of their own.

Thank you so much for taking the time the produce it.

Enjoyed reading it, and I’m sure I’ll read it again, there’s so much to learn here.

Thanks.

Thanks for navigating through it!

Johnathon this is a FAB article, I thourourghly enjoyed the read and learned loads, THANKYOU

Onward and upward LIVERPOOL.

Well said Sue! Thanks for reading and commenting, I appreciate it.

Fascinating. Great pics too

Thanks for reading the piece Kester, pleased you enjoyed it!

Final nail in the coffin was the Royal Mail ‘deal’ via a couple of southern based MP’s. But gladly they are back. And going from strength to strength.

Very interesting George – was that when Cunard finally moved their ‘RMS’ services south?

A superb summary of Liverpool’s rise and fall and rise again to its rightful position of one of the world’s premier passenger sea ports. We’re not quite there yet but Jonathan Brown’s elegant and incisive prose helps clarify where we are and helps to move this important renaissance forward, with the port’s history and his own current observations. The piece is also well illustrated with some fascinating photographs bringing the text to life. I never tire of looking at the Carbonara photo of the beautiful brand new RMS Olympic in the Mersey – the world’s largest manmade moving object, owned and registered in Liverpool, seen from the newly completed tower of the Royal Liver Building – Europe’s tallest building and innovative skyscraper.

Much appreciated Peter, I’ve been inspired by your own incomparable knowledge of all things ship shaped!

Good point about the image of Olympic taken from the newly finished Royal Liver clock tower – and on the same day White Star were launching Titanic – an extraordinary civic reach when you reflect on it.

But even at that point there were clouds on the horizon, with the three Olympic-class sister ships being scheduled from Southampton.

What a fabulous article. The decline of Liverpool’s maritime capabilities definitely left a major hole in our soul. It was short-sighted and some would say deliberate. Suddenly (thanks to the hard work of a select few) they are back and what a sight to behold. The majesty of these floating cities belongs in the heart of Liverpool, there is no finer sight than a “giant seabird” gracing the Graces and Liverpool in turn becomes a small part of every person on board. These beauties are not just our history but also our future.

Many thanks for reading through and leaving such a kind comment Dave.

You put it brilliantly – these beautiful ships are now our future as well as our past. I like your phrase, majestic ‘floating cities’ in the heart of our city – which then becomes a part of people, wherever they go.

An inspiring story of the revival of our traditional raison d’etre. Long may this resurgence continue. I am now looking forward to our first cruise holiday, on Boudicca, from Liverpool, later this year. Despite the current “cruise terminal” still being just a big tent, I understand the welcome for passengers from Angie Redhead’s team in Liverpool is second to none. How much more impressive this would all have been it could have taken place in the hallowed halls of the Cunard Building! Nevertheless, keep up the good work everyone!

Much appreciate your kind comment Rog – and fully agree that the Cunard Building would (again) make the finest passenger ship terminal of all time. Circumstances seem to be against it for now, but we live in hope.

What’s even more important than the building is the service and sense of welcome that passengers get, and that really is where the new Cruise Liverpool excels – there’s a general sense that all the staff, volunteer ambassadors, guides, coach drivers etc. are genuinely delighted to see people arriving here, and want people to have a good time.